Kenophilia

By Cristina Ramirez

An intimately connected triad arises here, around which my work revolves: the awakening of consciousness and the consequent development of the shamanic stratified cosmos, which weird fiction collects and adapts under its secular principles; Ligotti’s cosmic pessimism that entails a turn in the gaze disdaining the anthropocentric; and the catharsis of the cosmic sublime that Lovecraft develops in a world-without-us whose nature is raw and alien.

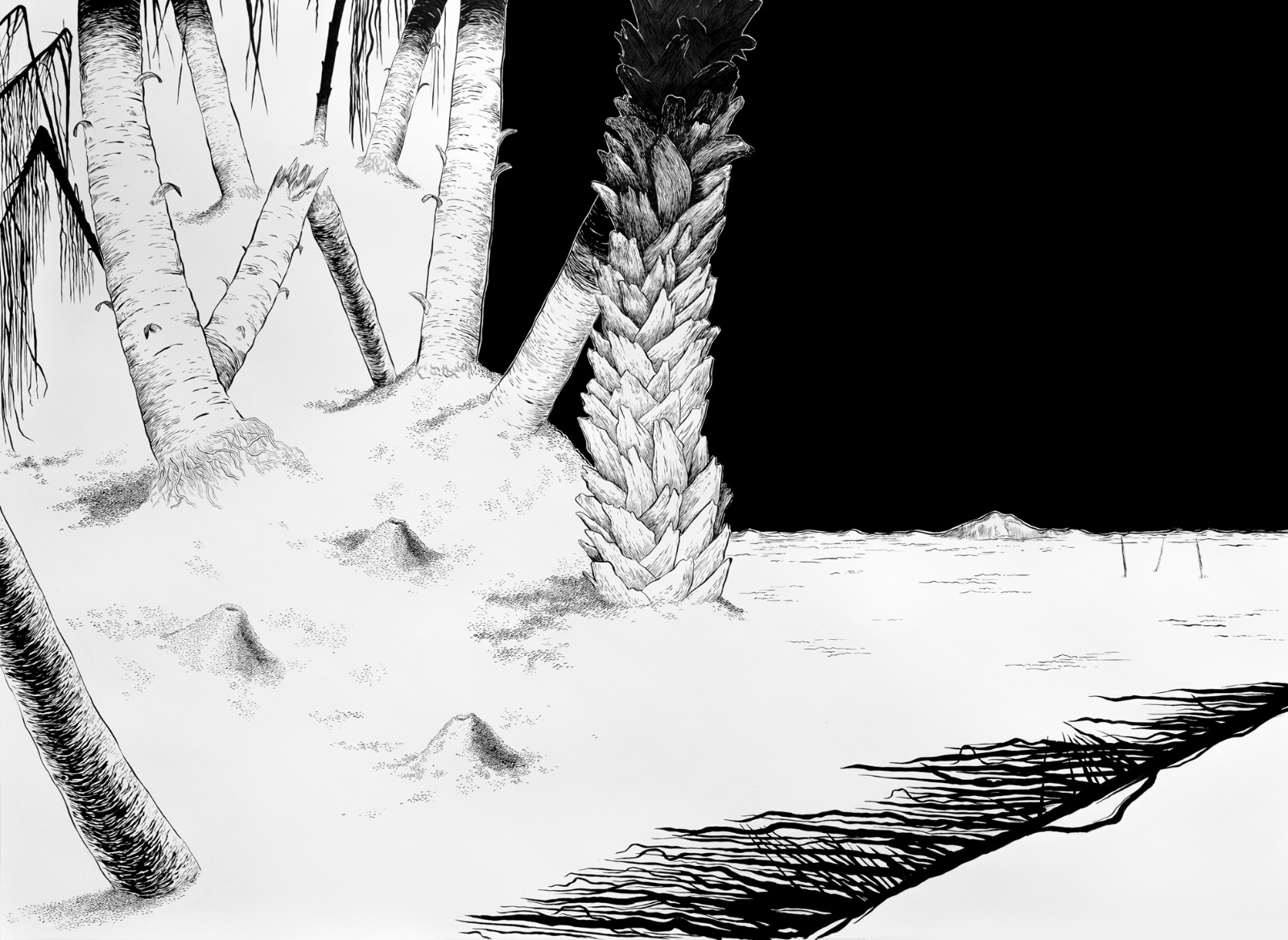

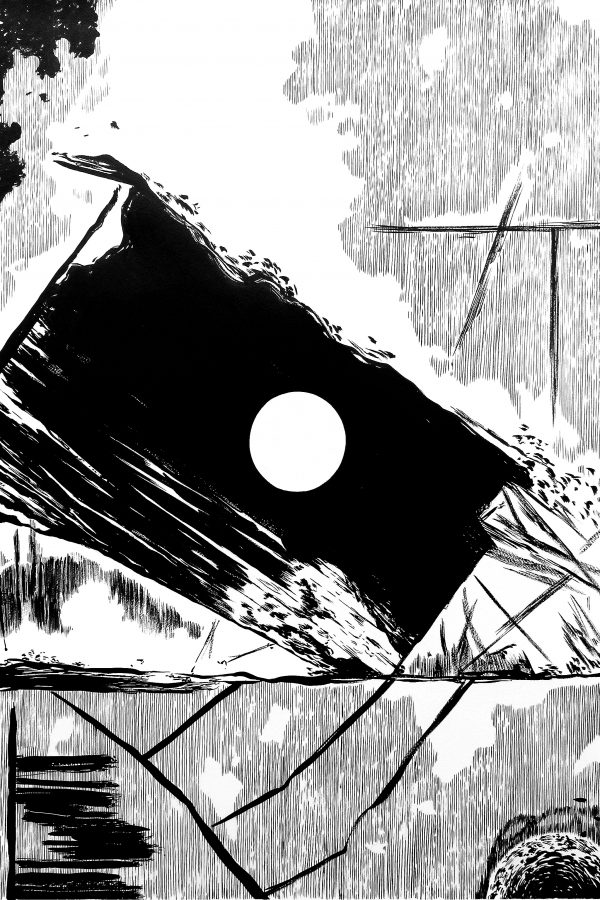

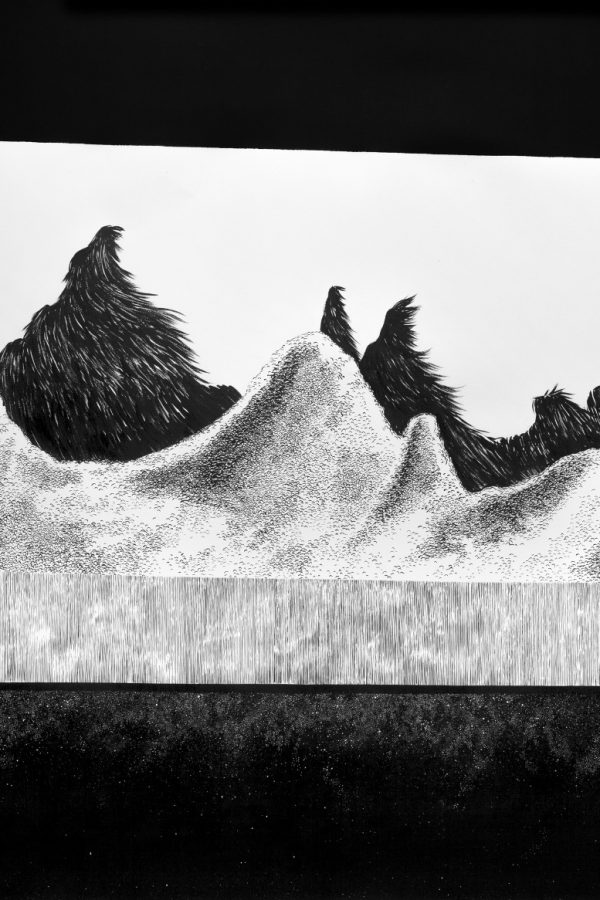

In Negro Humo (2016), the project I did for the second edition of the DKV Makma National Drawing Award (Spain), the images functioned as articulated impressions about the idea of fire. The drawings assembled the exhibition by accumulation and coexistence; repetitions, variations and alterations that, in the same way as in the oral tradition, made the discourse mutate and grow without ever losing sight of its genesis.

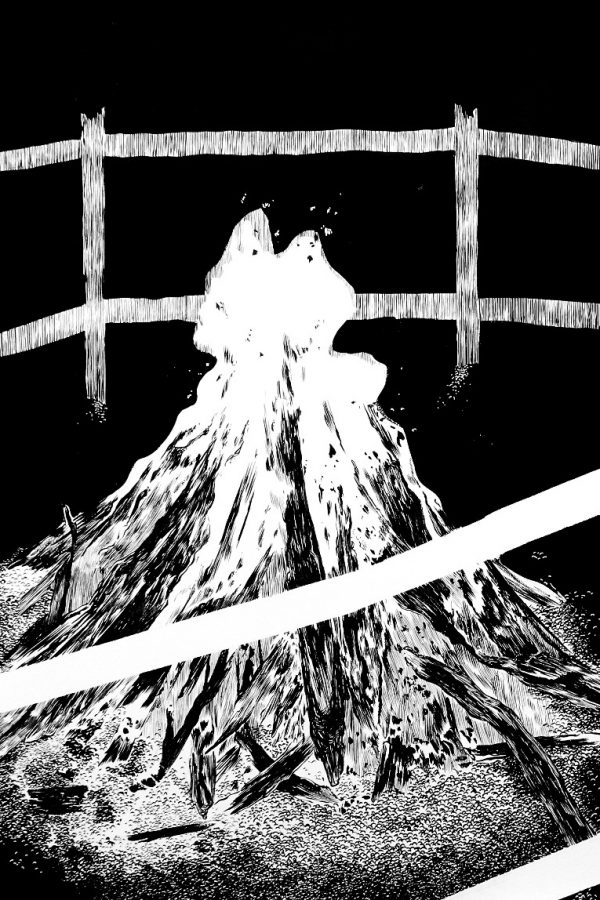

This project includes works such as The Hunt (2016) or “the ones from Outside” (2016) that are shown in the Marta Gualda Artifacts room. In them, the presence of fire evidences its delimiting capacity of space and, therefore, of thought and language. The limits drawn by light act as a magic circle, a border place that acts as a boundary between two worlds: the one we inhabit and that other, the cradle of the unknown, territory for myth and legend. The illuminated circle is interested in what is outside, what is not seen, this is what excites the imagination, which makes us fear the transgression of the logic of reality. Leo Perutz affirms that “the true fear, the true fear, is the fear of primitive man when he moved away from the glow of the bonfire to enter the darkness.” Perutz’s fragment refers to the well-known quote by Lovecraft in his essay on supernatural horror literature, in which the author underlines the essence of the genre in that debt to “the oldest and strongest emotion of humanity [which] is fear “, being that” the oldest and strongest fear is the fear of the unknown”.

This feeling of fear, a fundamental axiom of Black Smoke, is fundamental in the rest of the projects that I have developed to date.

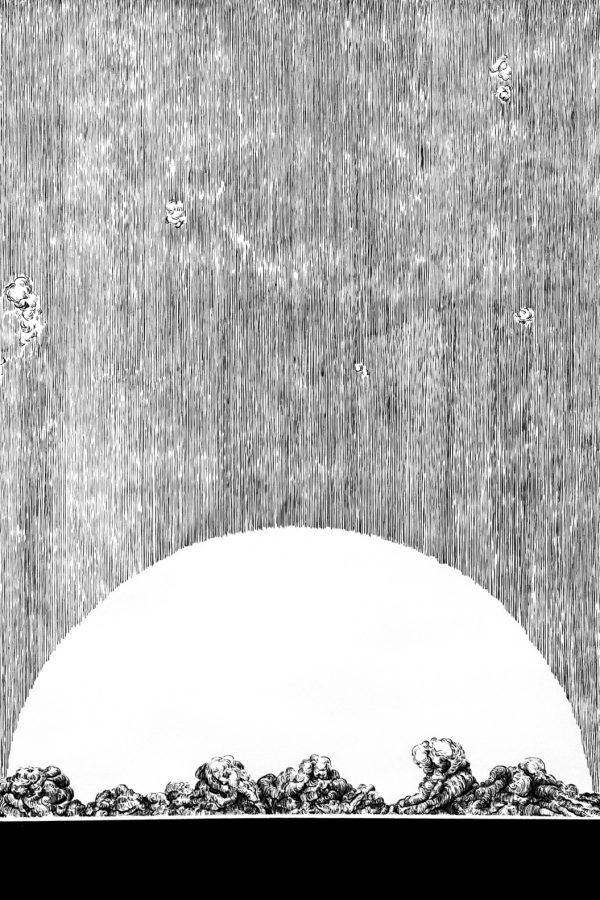

Paradigms of fear of the unknown, the unfathomable, will be the marine and cosmic abysses inheritance of the shamanic stratified cosmos that bursts into the Upper Paleolithic and seeps into the universal mythical, magical and religious world. From the experiences resulting from altered states of consciousness, experiences of flight to a higher spiritual realm, on the one hand, and experiences of underground and underwater travel to the underworld, on the other, shamans consolidate this symbolic scheme that they go through in the trance to bring the images of the supernatural world into the material realm.

In this mythical context the conscience is not condemning, one can still contemplate the abyss and look at the faces of the gods and the spirits that inhabit it. The shaman breaks through the vortex that leads him toward the sure vision of control of his supernatural power. Cosmic horror recovers this stratified cosmos, locating the supernatural again in higher and lower unfathomable corners, but empties the abyss and strips the vision, breaking the conscience when confronting it with the unthinkable. Witness that horror radically alien, not belonging to our world, leads to madness.

This insanity is what Ligotti presupposes in the human species if it were not for the deceit of that mother of all horrors that is conscience, a trap to which we submit so as not to perceive ourselves for what we are: «pieces of meat that are it spoils on disintegrating bones.

The writers who have orbited around the ideas of cosmic horror and pessimism, develop a series of narrative strategies to address the representation of what cannot be thought. In his essay Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy, Graham Harman looks at how these supernatural forces and beings present themselves when they tear apart our world. The author highlights two fundamental styles in Lovecraft’s narrative, two narrative orientations that will transcend his work: the allusive or vertical style, which addresses the supernatural through suggestions and omissions, and which avoids the direct style; and the cubist or horizontal, which juxtaposes numerous and unimaginable details in order to explain a totality. In my work, in an attempt to translate these ideas into a plastic language, the landscape appears as a receptor for the onslaught of these cosmic entities; the scene is torn and perverted when it comes into conflict due to the irruption of that alien world, under an excessively sharp figuration, tidy in details, that offers no rest to the gaze.

It could be said that most of my drawings or sculptures are threshold pieces: presences or intermediate spaces, the result of the intersection of these two worlds. In my works there is a conscious intention to exhaust the gaze, to remove its anchors, either because of a glut of graphic information, or because of a break with the single vanishing point – which forces the eye to wander from one side to the other, traveling the surface of the piece-, either due to a fracture in the narrative -which is given by the inclusion of geometry as an ellipsis or symbol of that other non-human nature-. The paradox thus becomes a constant by virtue of the desire to show the formless, the unthinkable and the unknown, through an excess of materialism.

Shop this Exhibition

-

Cristina Ramirez

Amateur, 2016

$3,400.00 Add to cart -

Cristina Ramirez

The Hunt, 2016

$2,200.00 Add to cart -

Cristina Ramirez

Green Star, 2016

$3,400.00 Add to cart -

Cristina Ramirez

Repose, 2016

$3,400.00 Add to cart -

Cristina Ramirez

It Is Still Burning, 2016

$2,200.00 Add to cart -

Cristina Ramirez

The Ones From Outside, 2016

$2,200.00 Add to cart